Hannah Barnard, an American Quaker in London, 1802

From this experience she saw the value of sharing faith and meeting houses with members of other denominations, not least Methodists. In London, at the 1799 Yearly Meeting, supported by a delegation of women Friends, she argued so tenaciously for the proposal to allow shared buildings that she was instructed to leave the meeting.

She travelled to Ireland where, unsurprisingly, Friends struggled with themes of violence and social order. More comfortable Friends cited the primacy of law and order; others, suffering and injustice. Questions coalesced around Old Testament accounts of genocide apparently legitimated by God’s command, set over against the Quaker peace testimony. A loose coalition of “New Lights” developed, arguing against doctrinal correctness and biblical literalism as normative. Barnard sided with them.

Barnard in London

Armed with an affirmative certificate from the Dublin Yearly Meeting, Barnard attended the Yearly meeting in London where she was ambushed by a minister from Ireland (who had nonetheless signed her certificate). He accused her “of unsoundness of faith on the subject of war,” (p.44 References are from Thomas Foster, An Appeal to the Society of Friends. Foster was a strong supporter of Barnard.)

The meeting adjourned to give Barnard the opportunity to reply. She declared war was “a moral evil... Which was pronounced heterodox; and that she was not one of the society for professing such an opinion.” (p.45). In response to further questioning she provided a written statement of her faith and declined to answer further questions. The minute stated:

“It having been made appear evidently to this meeting, that Hannah Barnard holds sentiments concerning some parts of the Old Testament contrary to the belief of the society, from its first rise to its present time, it is therefore the judgement of this meeting, that she has separated herself from them, and consequently it is highly improper that she should travel in the capacity of a minister among them; and it is this meeting’s advice to her to return home.”(p.48)

At the Morning meeting of ministers and elders on 9 June 1800 there was an attempt to throw her out as a “delinquent”. She refused to go (p.49). In a most peculiar move which smells strongly of an attempt at entrapment, the ministers present agreed to an open discussion with Barnard and “to lay aside all prejudice, and stand open to the clear discoveries of truth.”(p.50). Oddly, ministers brought in a man to bolster their side, who then admitted he was an atheist.

On June 20 a charge was laid against Barnard:

“That she promoted a disbelief, of some parts of the scriptures of the Old Testament, particularly those which assert, that the Almighty commanded the Israelites to make war on other nations. In which also she includes, the command given to Abraham, to offer up his son Isaac. It further appears, that she is not one with Friends, in her belief, respecting various parts of the New Testament, particularly relating to the miraculous conception, and miracles of Christ.” (p.59)

Again, she rebutted the charges in detail. She also made her own minute of the meeting which, it seemed, no-one else had done. And, again, the meeting found against her. It

“... recommends the said Hannah Barnard to desist from travelling, or speaking, as a minister of our religious society; but that she quietly return, by the first convenient opportunity, to her own habitation.” Signed by J.G.Bevan, Clerk (p.61).

|

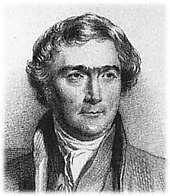

| Joseph Gurney Bevan (from Quakers Wikipedia) a cornerstone of Quaker evangelicalism and Barnard’s prosecutor, was to dominate English Quakerism for three decades (ODNB) |

Devonshire House Morning Meeting

On August 4 1800 the Devonshire House Morning Meeting was informed that Banard had not followed instruction nor returned home. On September 9 they articulated formal accusations against her:

She questioned various parts of the New Testament “particularly relating to the miraculous conception, and miracles of Christ.”

There was an important subtlety in this last charge. As the clerk pointed out to Barnard: “We have not charged thee with disbelieving any part of the New Testament, but only in differing in thy belief from the society; look at the charge and observe how it is worded.” (Ibid.)

Thus, the criterion for judgement was not the Bible, which each side could interpret, but the beliefs of the Society in relation to Scripture. These beliefs had never been codified. In practice, therefore, the beliefs of the Society were not distinct from the convictions of committee members.

This charge also changed the process: Barnard’s beliefs at large, her methods of reading and interpreting scripture, were no longer relevant to her defence. The only points which mattered were her interpretations of the specific passages of scripture in contention. Therefore the committee (which, for these purposes, embodied the society) only had to decide whether Hannah Barnard agreed with them. Self-evidently, she didn’t. Her detailed rebuttal of each accusation once again failed to persuade.

There were further meetings: on September 10th, 16th, and October 7th 1800. Nothing changed. The minute of the Devonshire House, Monthly Meeting of November 4th was clear only in repeating the advice that she return home. She would not go away so easily. She wrote to the subsequent meeting (December 9th) to give notice that she would appeal to the Quarterly Meeting.

Appeal

The 16 men appointed to hear Barnard’s appeal were empanelled on January 9, 1801. No-one was appointed who had been previously involved in the process or who had been overly partisan.

The case was presented to the panel in the form of the minutes of previous meetings. Again, this engrained a bias against Barnard, and it made the process a review, not an appeal. Barnard read the court her own detailed minutes. When asked to leave her papers she offered to write out a fair copy.

She had, she said, (pp132ff) been censured by a committee who had not “even alledged(sic) any unsoundness, or inconsistency in my professed principles, or conduct, as a justification of such proceedings.”(p132) and where discussion had been refused (p.133). She protested, and was told that proceedings had been regular and the advice proper, despite the facts that the committee was denied discussion of the issues and two committee members had refused to concur.

She charted the development of authorisation, and thus censorship, of publications by Friends and its perversion:

April 1801, Barnard in Ireland

Hannah Barnard attended the Annual Meeting of ministers and elders in Dublin and found little sympathy. She

London: Appeal against the judgement of the Quarterly Meeting

Barnard’s appeal to the Yearly Meeting was presented by Thomas Foster (the author of the book on which this account relies).

At the third session Bevan stated the charges as:

At the next session they adverted to the topic of war. Barnard “... did not believe, the God of love, … ever commanded any nation or person to destroy another by war.” (p.162) Her prosecutors produced a list of biblical texts in defence of war.

The fifth session continued the theme of war and moved onto miracles. At the sixth she made her case from respected Quaker authors of previous generations - Pennington, Barclay and Penn. Bevan responded that times had changed. She asserted that Bevan’s requirement of “a subscription to a full belief of the whole of the Scriptures, … as it was literally translated, that it was the pure truth of God;” (p. 167, iio) was itself a new thing in Quakerism.

At the seventh, Barnard extracted a concession: that she was “fully exonerated” over her views on Abraham. She complained about the informality of proceedings in the monthly and quarterly meetings. Bevan objected that she had kept her own minutes when the meetings had made none, and questioned their accuracy.

And then, with no concern for procedural justice, new accusations were laid:

Barnard expressed her “full belief in the resurrection; and that it rested in my mind, on far more substantial evidence, than any ancient history whatever.” (p.172) Bevan became abusive:

She asked the committee,

June 1, 1801, Yearly Meeting

Barnard, with one or two women Friends, if she so desired, was allowed to attend. After the report of the Committee of Appeals had been read, Barnard would be heard first followed by the respondents. In effect, the Yearly Meeting was also acting as a court of review.

The Committee of Appeals report stated,

Asked if she was satisfied, she replied “in a firm and audible voice, “I am not.” " (ibid.)

Barnard went back over the issues and the process, itemising her dissent, and concluding with the observation the committee had not in fact approved the charges against her, only

Bevan concluded

Barnard concluded with a plea: that Bevan had drawn unjustified inferences from her depositions, some of her statements had been misconstrued, and /221 that "works of approved authors printed and reprinted by the society justified her on every point on which she was charged with." (p.222)

Foster’s account goes on to specify the misrepresentations, procedural failings and injustices of the case against Barnard - but if publishing a critique after the event was cathartic, it made no other difference. Barnard returned home.

Act two

====

On August 4 1800 the Devonshire House Morning Meeting was informed that Banard had not followed instruction nor returned home. On September 9 they articulated formal accusations against her:

“That she promoted a disbelief of some parts of the scriptures of the Old Testament; particularly those which assert that the Almighty commanded the Israelites, to make war on other nations.”She also did not believe that God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac. (With the implication that, as the sacrifice did not happen, Barnard also appeared to accuse God of inconsistency.)

She questioned various parts of the New Testament “particularly relating to the miraculous conception, and miracles of Christ.”

“... that she is not one with friends, in her belief, respecting various parts of the New Testament, particularly relating to the miraculous conception, and miracles of Christ.” (p. 59; numbering added.)

There was an important subtlety in this last charge. As the clerk pointed out to Barnard: “We have not charged thee with disbelieving any part of the New Testament, but only in differing in thy belief from the society; look at the charge and observe how it is worded.” (Ibid.)

Thus, the criterion for judgement was not the Bible, which each side could interpret, but the beliefs of the Society in relation to Scripture. These beliefs had never been codified. In practice, therefore, the beliefs of the Society were not distinct from the convictions of committee members.

This charge also changed the process: Barnard’s beliefs at large, her methods of reading and interpreting scripture, were no longer relevant to her defence. The only points which mattered were her interpretations of the specific passages of scripture in contention. Therefore the committee (which, for these purposes, embodied the society) only had to decide whether Hannah Barnard agreed with them. Self-evidently, she didn’t. Her detailed rebuttal of each accusation once again failed to persuade.

There were further meetings: on September 10th, 16th, and October 7th 1800. Nothing changed. The minute of the Devonshire House, Monthly Meeting of November 4th was clear only in repeating the advice that she return home. She would not go away so easily. She wrote to the subsequent meeting (December 9th) to give notice that she would appeal to the Quarterly Meeting.

Appeal

The 16 men appointed to hear Barnard’s appeal were empanelled on January 9, 1801. No-one was appointed who had been previously involved in the process or who had been overly partisan.

The case was presented to the panel in the form of the minutes of previous meetings. Again, this engrained a bias against Barnard, and it made the process a review, not an appeal. Barnard read the court her own detailed minutes. When asked to leave her papers she offered to write out a fair copy.

She had, she said, (pp132ff) been censured by a committee who had not “even alledged(sic) any unsoundness, or inconsistency in my professed principles, or conduct, as a justification of such proceedings.”(p132) and where discussion had been refused (p.133). She protested, and was told that proceedings had been regular and the advice proper, despite the facts that the committee was denied discussion of the issues and two committee members had refused to concur.

She charted the development of authorisation, and thus censorship, of publications by Friends and its perversion:

“The reasons universally urged in favour of restrictive forms of doctrine, and licensers of the press, have ever been the preservation of an external appearance of unity in the church; which instead of promoting in any degree the avowed purpose, have as universally been converted into engines of tyranny and oppression.” (p.137)

April 1801, Barnard in Ireland

Hannah Barnard attended the Annual Meeting of ministers and elders in Dublin and found little sympathy. She

“rose, and expressed what was on my mind; in doing which, I felt sweet peace, and the meeting appeared quiet, and generally solid, so far as I observed. … “ (p.145)One unkind Friend informed the meeting that she had been advised to cease speaking as a member of the society.

London: Appeal against the judgement of the Quarterly Meeting

Barnard’s appeal to the Yearly Meeting was presented by Thomas Foster (the author of the book on which this account relies).

Bevan was chief ‘prosecutor’. Barnard objected to three members of the panel as they were also members of the Morning Meeting which, officially, was the body bringing the case. She was overruled. There were to be nine sittings of the court between 23rd and 30th May 1801.

At the second sitting:

At the second sitting:

“.... Richard Phillips asserted, that I not only laid waste, a great part of the Old Testament, both Pentateuch and Prophets, by the unavoidable consequences of my avowed sentiments on war; but that I fell short even of Mahomet, in my professed belief in Christianity; so far as related to the miracles recorded in the New Testament.

That by declaring my disbelief, that the Almighty ever commanded any nation, or person to destroy another; of course I did not believe the accounts recorded of the many miracles that were wrought, to enable the Isrealites to conquer their enemies.

In short I made those records of no validity; and in effect laid waste, nearly the whole of the Scriptures; and therefore, if I had the least claim to the character of a minister among Friends, he knew not how to distinguish black from white."

To which J.G. Bevan fully assented: saying, ‘In short she makes out Moses, to be a fool, or a very great liar.’ ” (p. 154; iio)

At the third session Bevan stated the charges as:

“I [Barnard] made Moses a deceived deceiver; and by that means, I impeached the character of Jesus Christ also; by advancing the sentiment, that it was incompatible with the divine character, to command any nation, or person, to destroy another;” as “that Christ evidently approved of the Jewish law, for inflicting the punishment of death, for disobedience to parents expressly calling it the law of God.” also by calling into question “the divine sanction of the Jewish wars, and their sanguinary laws.” (p.156, iio)

At the next session they adverted to the topic of war. Barnard “... did not believe, the God of love, … ever commanded any nation or person to destroy another by war.” (p.162) Her prosecutors produced a list of biblical texts in defence of war.

The fifth session continued the theme of war and moved onto miracles. At the sixth she made her case from respected Quaker authors of previous generations - Pennington, Barclay and Penn. Bevan responded that times had changed. She asserted that Bevan’s requirement of “a subscription to a full belief of the whole of the Scriptures, … as it was literally translated, that it was the pure truth of God;” (p. 167, iio) was itself a new thing in Quakerism.

At the seventh, Barnard extracted a concession: that she was “fully exonerated” over her views on Abraham. She complained about the informality of proceedings in the monthly and quarterly meetings. Bevan objected that she had kept her own minutes when the meetings had made none, and questioned their accuracy.

And then, with no concern for procedural justice, new accusations were laid:

Richard Phillips “made some farther charges against me, respecting my sentiments on miracles, alleging that they very nearly amounted to a denial, of the whole of them, and consequently I denied the resurrection. So that in fact he held me up to the committee, as a compleat infidel.” (p.171, iio)

Barnard expressed her “full belief in the resurrection; and that it rested in my mind, on far more substantial evidence, than any ancient history whatever.” (p.172) Bevan became abusive:

“You may see by this instance, how slippery she is, and how narrowly she needs watching; she now alludes to the doctrine of the resurrection, intending at the same time to make us believe, she means to allude to the bodily resurrection of Christ.” (ibid.)

She countered that she did not question the bodily resurrection of Christ. Furthermore, she believed in the resurrection of both the just and the unjust, although how and in what form was beyond human knowledge.

At the eighth sitting (p.174) Barnard read her summary of the matters at issue. Bevan wished to see it. She said she would read it again.

At the eighth sitting (p.174) Barnard read her summary of the matters at issue. Bevan wished to see it. She said she would read it again.

“He replied, in apparent disturbance of temper, I do not request it, I demand it as my right; and if thou refusest it, I shall only desire the committee to take notice of that refusal.” (p.176)

She asserted it was not within his rights to have a copy. The committee had set the precedent by not letting her have a copy of the appeal and he had refused to give her a written copy of the charges he and Richard Phillips had made to the committee, and which they continued to refuse to retract. Bevan backed down with bad grace, saying

“... but the committee may see, how tricky she is, and how /p177 willing to be reading her papers, even seven, or ten times, if we would be willing to sit and hear them.”(iio)

She asked the committee,

“Do you clearly understand me, that I fully distinguish, in point of essentiality, between doctrinal truths, and historic facts; or, in other words, contingent truths, however well attested by outward evidence; such as in the common course, and order of Providence they depend on?“They answered, yes: And soon after adjourned.”(p178)

June 1, 1801, Yearly Meeting

Barnard, with one or two women Friends, if she so desired, was allowed to attend. After the report of the Committee of Appeals had been read, Barnard would be heard first followed by the respondents. In effect, the Yearly Meeting was also acting as a court of review.

The Committee of Appeals report stated,

“… that it appears to us, that the said Hannah Barnard does not unite with our society, in its belief of the holy Scriptures; the truth of which, in several important instances, she does not acknowledge, particularly those parts of the Old Testament which assert, that the Almighty commanded the Israelites to make war upon other nations, and various parts of the New Testament, relative to miracles, and the miraculous conception of Christ.”

We are therefore unanimously of the judgment, that the said quarterly meeting is fully justified, in confirming the judgment of the monthly meeting of Devonshire House, and its advice to the said Hannah Barnard.” (p.185)

Asked if she was satisfied, she replied “in a firm and audible voice, “I am not.” " (ibid.)

Barnard went back over the issues and the process, itemising her dissent, and concluding with the observation the committee had not in fact approved the charges against her, only

“the recommendation … [that I] desist from travelling, or speaking as a minister of our society, and only advises me to return home.” (p. 197)

In so doing the committee had avoided the substance and dismissed the person.

She also pointed to a procedural injustice: that several of her judges, as members of the yearly meeting of ministers and elders, had thereby also been her accusers. This rendered them “utterly ineligible to act as judges of her appeal.”(p.199)

In fact, she said, it was her accusers’ attitude to war which undermined the Friends’ “well-known testimony against all war”. She asked whether the “iniquities and cruelties of war” could have had God’s approbation. (p.200)

She acknowledged the power of God to effect miracles. As to the virgin birth, she had been reported as telling the committee that she had had no revelation on the issue. “Are ministers usually given such a revelation?” she countered (p.201). Her judges had ignored her statement that she acknowledged the power of providence to effect miracles. “And” she concluded rhetorically, “is the above sufficient to outweigh their statement that ‘I appeared to be closely united to the society in a firm belief, of inward manifestation of the divine will.’ “ The committee, she concluded, “endeavoured to convince me, of the propriety of Friends’ sentiments, upon these points, whereon I seemed, not to agree with them.”(p.202)

The committee sat again at 4pm that day. Bevan’s summary was that the issue in question was the interpretation of Scripture. Barnard’s belief that God never “commissioned any nation, or person, to destroy another; but that they were formerly, as at present, only permitted to do so.” was incompatible with many Old Testament passages and the authenticity of the whole Pentateuch. Consequently (in what appears to have been Bevan’s favourite phrase in these proceedings) she made Moses ‘a deceived deceiver’ (p.209).

Summing up, Bevan asserted that

She also pointed to a procedural injustice: that several of her judges, as members of the yearly meeting of ministers and elders, had thereby also been her accusers. This rendered them “utterly ineligible to act as judges of her appeal.”(p.199)

In fact, she said, it was her accusers’ attitude to war which undermined the Friends’ “well-known testimony against all war”. She asked whether the “iniquities and cruelties of war” could have had God’s approbation. (p.200)

She acknowledged the power of God to effect miracles. As to the virgin birth, she had been reported as telling the committee that she had had no revelation on the issue. “Are ministers usually given such a revelation?” she countered (p.201). Her judges had ignored her statement that she acknowledged the power of providence to effect miracles. “And” she concluded rhetorically, “is the above sufficient to outweigh their statement that ‘I appeared to be closely united to the society in a firm belief, of inward manifestation of the divine will.’ “ The committee, she concluded, “endeavoured to convince me, of the propriety of Friends’ sentiments, upon these points, whereon I seemed, not to agree with them.”(p.202)

The committee sat again at 4pm that day. Bevan’s summary was that the issue in question was the interpretation of Scripture. Barnard’s belief that God never “commissioned any nation, or person, to destroy another; but that they were formerly, as at present, only permitted to do so.” was incompatible with many Old Testament passages and the authenticity of the whole Pentateuch. Consequently (in what appears to have been Bevan’s favourite phrase in these proceedings) she made Moses ‘a deceived deceiver’ (p.209).

Summing up, Bevan asserted that

“questioning, or rejecting these parts as not being literally true, leads necessarily to a denial of the general authenticity of the whole of the Scriptures, considered as a true record.” (p.211).

Implicit in this accusation was the idea that scripture should be regarded as a sheet of glass: to break one bit is to shatter the whole.

Second, Barnard was a fraud: she

Second, Barnard was a fraud: she

“... has done much pretending to the spirit, by crossing the seas, and travelling to free the gospel from ancient and modern corruptions; that is, in fact, to inculcate a disbelief in the Scriptures.” (p.213)

Insofar as she rejected the virgin birth of Jesus along with other miracles - either in themselves or as proof of Jesus' divine mission - it was evident, he asserted, that Barnard did not agree "with the Society in admitting the truth of those facts, as they were related in the Scriptures..."(p.214).

Bevan concluded

“... it is not so much properly the question, whether the society or the appellant was right, but whether there was not such a discordance in sentiment between them, as to render it unfit for her, to exercise the office of a Christian instructress, sanctioned and approved by the society; …” (p.218)

without, apparently, the shift in his grounds for complaint being noticed.

There is a fundamental irony of the conflict between Bevan and Barnard: both were sure they were right, and the rightness of one could not co-exist with the rightness of the other.

There is a fundamental irony of the conflict between Bevan and Barnard: both were sure they were right, and the rightness of one could not co-exist with the rightness of the other.

“J.G. Bevan now rose, and observed, in the language and tone of triumph, that he thought the meeting was now furnished with a key to Hannah Barnard’s divinity; which was to form an absolute rule of right, and wrong in her own mind, and to reject everything, that did not square with it; for, says he, it appears by what she has openly declared before us, that she believes nothing she cannot comprehend with her reason, or whatever else she may call it. She will not believe things because she finds then written in the Scriptures; or because others ever so generally believe them. She will not believe, unless she has evidence in her own mind, that a thing is true.”(p. 220, iio There is a need for a little caution: the italics were applied by Foster to his notes of Bevan's speech.)

Barnard concluded with a plea: that Bevan had drawn unjustified inferences from her depositions, some of her statements had been misconstrued, and /221 that "works of approved authors printed and reprinted by the society justified her on every point on which she was charged with." (p.222)

And yet, when Bevan opined on divinity, he too was right: his mind and that of the society were (increasingly) one and the same. Both he and Barnard knew with the same certainty that they were faithful and true witnesses, but Bevan held the power and Barnard was the outsider.

Foster’s account goes on to specify the misrepresentations, procedural failings and injustices of the case against Barnard - but if publishing a critique after the event was cathartic, it made no other difference. Barnard returned home.

Act two

What seemed like a conclusion turned out to be no more than an intermission. The trial ended with an instruction to six of its members, including Bevan,

to take copies thereto of the foregoing Minutes and to see that copies of the proceedings of the several meetings in the case of Hannah Barnard be speedily transmitted to the Monthly Meeting of Hudson in the State of New York. (Foster, T. (1804).

The papers arrived before Barnard.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments and corrections are welcome. But please note that the focus is on the historical examination of heresy cases, not the rights and wrongs of the theology..